Guest blogger Joshua Raclaw is a linguist and conversation analyst who works on the use of language in meetings and everyday conversation.

As a linguist who specializes in discourse analysis, my research forces me to pay attention to some of the smallest details of how language unfolds during our everyday conversations. I lovingly obsess over every like and um, every pause and silence, and all of the intricate ways that our speech aligns with how we gesture or laugh or shrug our shoulders, because all of these small pieces of the interaction fit together to help give meaning to language. And so I am one hundred percent with former FBI director James Comey when he says, “Lordy, I hope there are tapes.”

My colleagues will tell you that there is nothing glamorous about the type of work we do to prepare a transcript for discourse analysis. It is tedious and anal retentive to the extreme, and you often listen to the same stretch of talk again and again to try to get things right. Even then there can be problems. Despite the luxury of using high-quality digital recordings to transcribe the words exactly as we hear them, it’s not uncommon to get things wrong. If you’ve ever watched television with the captions on, you know exactly what I’m talking about: Words frequently get mistranscribed or omitted completely, and it’s even worse when the transcriber is working with a live television feed and they can’t go back to double-check what was said. In short, language moves pretty fast, and if you don’t stop and look around once in awhile, you could miss it.

This is why I’m so interested in James Comey’s account of his interactions with Donald Trump, because we’ve been so focused on the exact wording of their exchanges. The version that we get from Comey’s prepared statement goes like this: “[Trump] then said, ‘I hope you can see your way clear to letting this go, to letting Flynn go. He is a good guy. I hope you can let this go.’” At Comey’s Senate hearing, there was a significant focus on the precise meaning of those words. While Comey agreed that Trump did not literally “direct” him to let the issue go, Comey also acknowledged that he understood Trump’s words as a direct order to drop the investigation of Michael Flynn. Fellow linguist Deborah Tannen has recently written on this very issue, and she makes a strong point in highlighting the importance of the indirectness of language, what she terms its metamessage, to argue that Trump’s words are in fact hearable as a directive despite their literal phrasing as things Trump “hoped” would happen. Both Tannen and linguist Bill Labov have also argued against the idea floated by New Jersey governor Chris Christie that Trump’s words were just an innocuous example of “normal New York City conversation”, while linguistic anthropologist Jena Barchas-Lichtenstein dove a bit further into the issue of context in closely analyzing Trump’s words to Comey. Linguists are experts in examining the meaning and function of language, and it’s no surprise that we’ve taken an interest in the precise words used by Trump– and the possible obstruction of justice charges that may hang in the balance.

I’m also interested in the details of the exchanges between Trump and Comey, but I’m most interested in the way that we have collectively understood Comey’s recollection of what Trump said during their private meetings. Despite Trump first teasing the existence of audio recordings of these conversations over a month ago, the Trump administration has yet to release them, and a Freedom of Information Act inquiry on behalf of the Wall Street Journal has recently confirmed that they have no recordings of Trump’s conversations made in the White House. Both the Senate’s and the public’s understanding of Trump’s words to Comey—and in particular, Trump’s “I hope…” statements—thus come not from direct recordings of their exchanges, but rather from memos transcribed by Comey directly following his interactions with Trump. Comey has described how he penned these memos the moment he returned to his car following their meetings, and I’m interested in how details like this have helped us to collectively treat Comey’s after-the-fact transcriptions of these conversations as if they offer verbatim accounts of what Trump said to him.

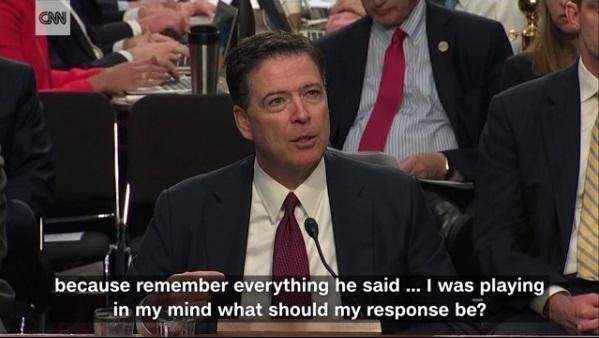

Let’s go back to my earlier point about the problems that discourse analysts face when we transcribe conversation, namely that it can be hard to always get things right. Sociologists, anthropologists, psychologists, and scholars across the humanities have written at length about the unreliability of memory (this explains why we incorrectly think that Darth Vader said, “Luke, I am your father” and also why conspiracies abound about the correct spelling of “The Berenstain Bears”), and discourse analysts know the unique ways that this unreliability extends to the work of remembering, and faithfully capturing, the details of how conversations unfold. Let’s look at an example of what I mean here, taken from the Senate hearing where Comey gave his famous line about hoping that there are tapes. When I first searched for video of the hearing, I saw that CNN offered a version with captions (good on you, CNN). Let’s take a look at how these captioners transcribed the following bit of talk said by Comey: “And look I- I’ve seen the tweet about tapes.”

We see an omission and a mistranscription here: CNN has done away with Comey’s sentence-initial “and look”, and they’ve mistranscribed his singular “tweet” to the plural “tweets”. They’ve also gotten rid of Comey’s mis-start when he said “I- I’ve seen the tweet”, but that’s pretty standard for captioning work. Now, if you listen along with the audio of Comey, you’ll hear that what he says is actually pretty clearly articulated, and so we can’t pin the mistranscription on unclear audio in this particular case—though we often can. For example, just a few seconds before the quote above we get some pretty rapid speech from Comey where he says something like “‘cause I was gonna remember everything he said” or possibly “‘cause I wanted to remember everything he said”.

The CNN caption instead has Comey saying “because remember everything he said”, and so it just does away with that little stretch of not-entirely-clear speech, though that doesn’t make the full account of what Comey really said any less important to either the speaker or to the audience. We also see that CNN has mistranscribed “every word” as “everything”, despite Comey’s speech being pretty clear by that point. NPR does better by Comey, transcribing his speech as “’cause I could remember every word he said”, but let’s go back and listen to the video again. Play that snippet of Comey’s testimony a dozen times (or two dozen, for good measure) and you can hear that Comey clearly says too many syllables for NPR’s transcription to be right. I hear the most likely candidate as “‘cause I was gonna remember everything he said”, but even then I’d want to have a few discourse analyst colleagues have a go at independently transcribing Comey’s talk before I made any definitive claims about it.

Now the transcription issues in the latter example are arguably minor, to be sure: Whether Comey said “I was gonna remember” or I wanted to remember” or “I could remember”, the same general sentiment is there. However, these transcription issues get more important if we go back to the first example of captioning by CNN, where they omit Comey’s “and look” entirely. Discourse analysts like Galina Bolden and Jack Sidnell have written about the importance of how little words like “and” or “look” can change the meaning and interpretation of the sentences that follow, and CNN’s mistranscription strips away those important details. But more importantly, the examples of transcription errors we see in both of the examples above show how easy it can be for even trained transcribers to lose the details of what was said, even when these professionals can listen again and again to a recording.

By comparison, Comey’s memos detailing his interactions with Trump had him recalling Trump’s exact wording only after the fact, and that offers an even bigger challenge in capturing an entirely accurate account of their exchange. Yet discussions of Comey’s recollection of his exchange with Trump, and Comey’s portrayal of Trump’s exact words, have treated these recollections as if they were the verbatim representations of what Trump said during these exchanges.

Why have we given Comey’s words that power? And what can we take away from all this? For starters, it’s worth acknowledging that, while there is reason to believe that Comey may not have gotten every word of their exchange correct, he also did the best he could with the resources available to him. Comey clearly took care to ensure these representations of Trump’s words were as accurate as possible. The fact that he penned these memos immediately following the conclusion of his meetings with Trump is telling, and during Comey’s Senate hearing he stressed that one of the reasons he didn’t challenge Trump’s indirect order was because he was actively working to remember Trump’s exact words to him. Studies have shown that language really does move pretty fast, and it would arguably have been tough to keep Trump’s exact words in mind and still conduct the face-threatening work of challenging what he heard as an order from the Commander-in-Chief. And it’s not as if social scientists haven’t engaged in similar methods to Comey’s after-the-fact memos: linguistic and cultural anthropologists routinely make use of after-the-fact fieldnotes describing their interactions with others that may only be written down at the end of a long day, a far greater gap than Comey allowed for when he dashed to his car to jot down the details of his conversations with Trump. But linguistic anthropologists also do significant work to get these details on paper just after they occur, like the time that William Leap transcribed the details of recent conversations on napkins at a dinner party. So while discourse analysts know that the ultimate accuracy of Comey’s memos can only be checked against any possible recordings of his interactions with Trump, Comey has also done work to position himself as an authority on their exchanges, and this authority can only really be challenged by comparing Comey’s memos to the tapes that we’ve been hearing about for a number of weeks now.

And so, speaking as a discourse analyst? Lordy, I hope there are tapes.

Pingback: Two linguists explain why calling the Ukraine memo a “transcript” is so wrong – Yakanak News

Pingback: Two linguists explain why calling the Ukraine memo a “transcript” is so wrong - CrimeStopNews.Com